The Gin Acts and The Origin of Old Tom

Following the surge of making gin in the Gin Craze, parliament passes a series of major Acts designed to control the consumption of gin between 1729 and 1751. The first Acts attempted to curtail consumption through high retail taxes and prohibitively expensive annual licenses to sell gin. By 1736 the sale of gin was virtually outlawed.

However, after an initial fall, illegal sales resulted in an estimated 30% increase in production (of an ever more unreliable and often poisonous spirit) until, by 1743, the English were estimated to be drinking an impressive 10 litres of gin per person per year!

It was during this period, according to the self-serving (and probably quite unreliable) memoirs of a certain Captain Dudley Bradstreet, that we find one of the earliest vending machines and, according to legend, the origins of the name Old Tom to describe the sweet style of gin that was popular throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

Having studied the legislation, Captain Bradstreet thought he had worked out a way to sell gin without having to pay the £50 annual license.

His cunning plan was to purchase a wooden plaque shaped like a cat (an ‘old tom’) and drive a lead pipe through it. He put the word about that if someone needed a shot of gin that should knock on his door and whisky “Puss” through a slot in the plaque. If there was gin for sale the reply would be “Mew” and the punter could push their coins through the cat’s mouth. The gin would then be delivered through the lead pipe.

Whether it really originated with Captain Bradstreet is uncertain, but the practice spread and these ‘Puss-and’Mew’ shops soon appeared throughout London. They were never actually legal, but the Gin Act didn’t give the police the authority to enter buildings selling gin and they instead had to rely on informers. As the person selling the gin was hidden in the house, informers were unlikely to say who they were!

In fact, it was the use of informers that fatally undermined the 1736 Gin Act. On the one hand, with so many Gin Shops to report, it simply became too expensive t pay them the promised £5 each time they were able to tell the authorities who was selling the gin. On the other hand, violence towards any informers caught by the mob often got out of hand. Riots were not uncommon. The 1736 Gin Act was repealed in 1743 and subsequent legislation focussed on distilleries rather than retailers.

Courtesy of the Californa State Archives

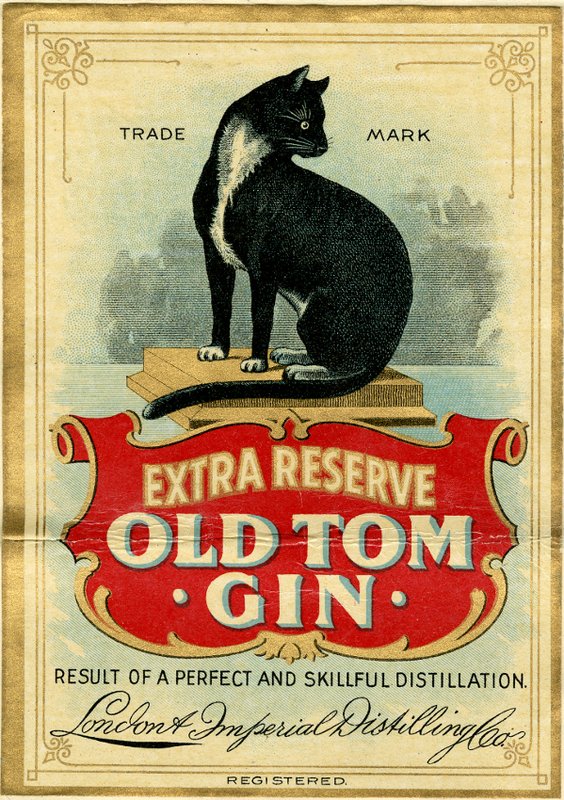

An advert issued in 1899, Old Tom Gin, Wreden, Kohlmoos Co.

This seemed to be more successful in curbing excessive gin drinking, although this was probably also due to wider economic trends. With increasing grain prices and falling wages, the ‘gin craze’ was effectively over by 1760.

In our next article in this series we look at the development of distillation techniques, the emergence of gin palaces and a move towards a more stylish spirit.